Writing, ranting and the national decline

“All I have is these words which I give to you, because all we have is each other.”

Poet and social philosopher, Athol Williams’ closing lines of his poem, “These words”, were an apt ending to a multi-themed and audience-engaging conversation - between five writers of words - about South Africa’s political and social situation.

When Lowveld Book Festival organisers invited the group of incredibly interesting but completely unique authors - and social commentators in their own right - to sit around a table on stage in August, and share their opinions, the audience in the Barnyard Theatre, White River, knew they were in for an intellectual treat.

Well-respected journalist and natural orator, Gus Silber, discussed politics, the state of the nation and everything else in between with fellow authors Richard Pithouse (Writing the Decline), Dale McKinley (SA’s Corporatised Liberation), Sizwe Yende (Eerie Assignment) and Williams who has also written his autobiography, Pushing Boulders.

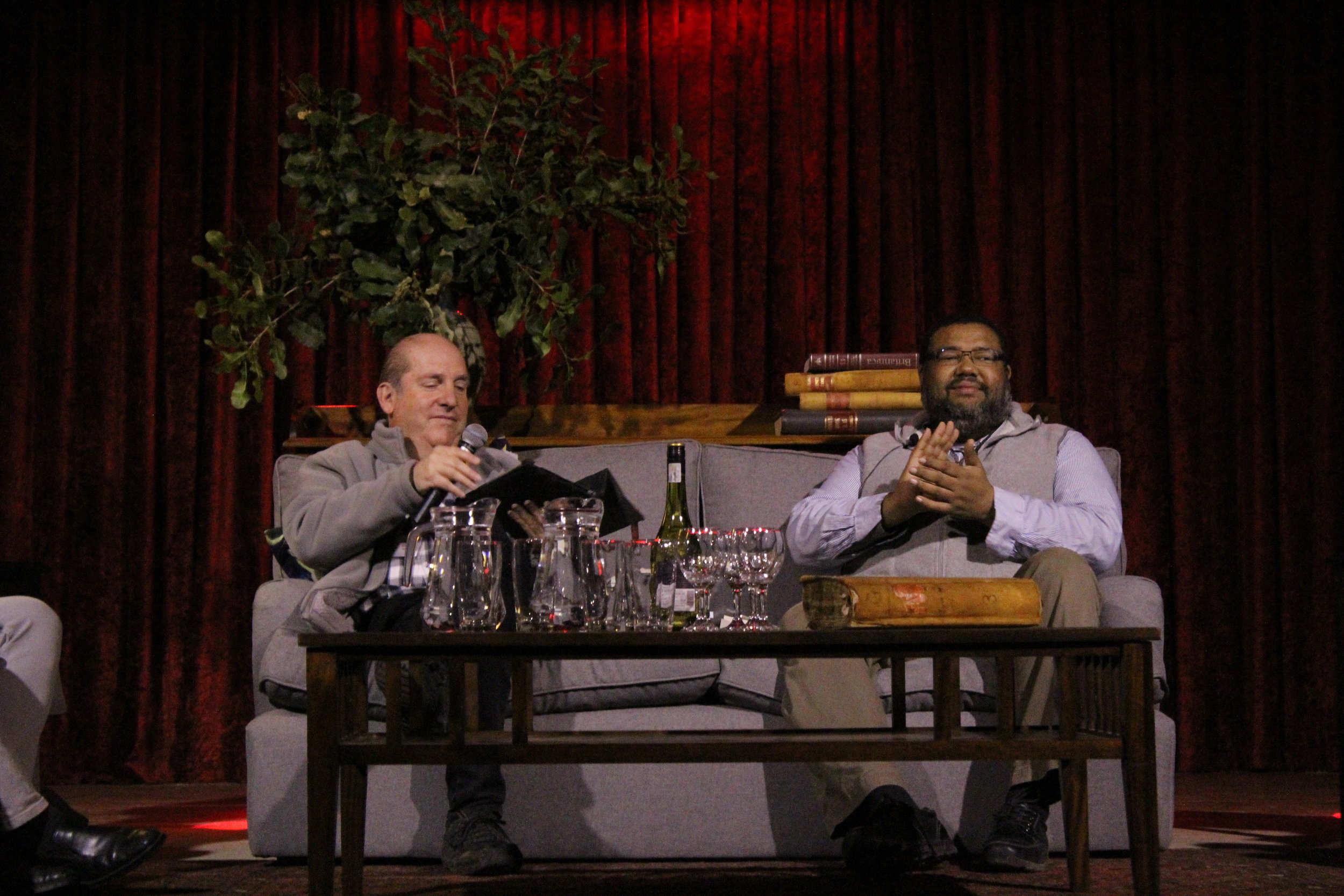

Sizwe Yende, Dale McKinley, Gus Silber, Athol Williams and Richard Pithouse.

Three months later, we hear of yet another political scandal or “State Capture” related revelation almost daily. What was said then is just as pertinent now.

The topic for the panel discussion, “When things fall apart – can writing and ranting help to reverse our national decline?” was inspired by the poem “The Second Coming” by William Butler Yeats.

““Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world…”

”

It is said that it is the poet’s vivid, violent imagery and description of the virtual collapse of society caused the prose to be one of Yeat’s most anthologised poems, but also one of the most difficult to understand.

But with Silber at the helm, there was certainly no confusion as to where the panel discussion was heading.

He led the speakers through their personal journeys, their careers and most importantly, their writing. There was an overwhelming consensus between all parties that since 1994, there had not been much of a change in the economy of South Africa, nor in the socio-political situation of her people.

Researcher, lecturer and author of four books, Dale McKinley’s latest offering, SA’s Corporatised Liberation: A critical analysis of the ANC in power, deals with the analogy that South Africa is a house with a rotten foundation, and that the penthouse suite is occupied by the economic landlords . The Gupta family just happen to be its current tenants.

“State capture happened from the early 90s. We got a new paint job for the house, but (it) is crumbling. Nothing has changed,” McKinley said.

He added that if socio-economic equality is not addressed, and soon, South Africa might find itself in the throes of a civil war, when “the 1980s will seem like child’s play”.

Rhodes politics lecturer and widely-published journalist, Richard Pithouse agreed that many people in this country are yet to attain democracy as it was promised.

His published collection of essays entitled Writing the Decline: On the Struggle for South Africa’s Democracy is written about Durban and Grahamstown, where the political landscapes greatly differ.

“One problem with politics and journalism today is that we don’t understand what is happening just a few hundred kilometers away. KZN is where the future of this country will be decided. There is an unbroken history of violence which moved into post-apartheid South Africa, where political assassination is routine (practice),” Pithouse explained.

He also said if the current issues were not addressed, South Africa could end up like states such as Mexico or Columbia.

Silbur asked Pithouse if he thought the Fees Must Fall movement had influenced the teaching of politics at tertiary institutions such as Rhodes University, to which the academic responded that the movement had been lost, “smashed by various actors”.

““The struggle played out differently across the country. In 2015, we felt a moment of possibility. At the moment, I don’t see any strong force.””

He added that although the outlook of students had changed over the years, the university’s academic material had stayed similar.

For Sizwe Yende, Mbombela-based journalist and author of Eerie Assignment, it is corruption among the country’s leaders which he believes is at the forefront of the nation’s problems.

His book deals with his “nightmare as a journalist in Mpumalanga”; being offered bribes to keep mum on certain issues, exposing the atmosphere of political fear in the province, and having his life threatened on more than one occasion.

““Politicians are not there for (you and I). Politicians are there to benefit for themselves. If we want to nip corruption in the bud, we need people who go into politics because they want to serve their country, not in order to earn an (impressive) salary.””

"We want leaders who have other jobs or professions to go back to so that they do not cling to power," Yende said.

Williams, who was born in 1970 in Mitchell’s Plain, Western Cape, and who remains involved in that same community today, admitted the saddest thing is that South African people have become so cynical.

But it was not all doom and gloom. Williams does not understand why we almost seem to bow down to democracy in this country.

“I see democracy as a means to get where we want to go. There is despair, but also immense beauty, and when I started to see that beauty, it gave me a reason to draw people into something hopeful,” he said.

“Not only should my work be a mirror to society, but also a way of looking forward and painting a picture of what could be.”

Silber’s final question to his contemporaries was whether they felt a duty as writers to keep things from falling apart.

Yende explained that his journalistic writing was a small contribution “to sustain the democracy we do have”.

“I am an activist for democracy, as I cannot be seen to be an activist of anything else. I have to avoid taking sides in order to be objective. But I write for readers to make informed decisions,” he said.

Political activist McKinley, who was expelled from the South African Communist Party for disagreeing with the direction in which the party was moving, and as some say, actually trying to be a communist, said without dissent, we could not move forward as a people.

““We’ve lost the dream to change, we’re paralysed. I think we should all be dissenters. Writing is just one form of dissent. I firmly believe that as human beings, we can make our world better. I write to catalyse that change.””

After all, what we have is words and each other.